The Women’s Place conducted a survey to assess the COVID-19 remote work experiences of The Ohio State University employees in May 2020. The report provided below summarizes responses from nearly 1,700 staff and over 600 faculty. We encourage university partners to use this information to create supportive work practices and promote gender equity amid changing work conditions during COVID-19.

Summary Report of Faculty & Staff COVID-19 Remote Work Experiences

This report distills the key findings of an anonymous survey designed in consultation with the President and Provost’s Council on Women (PPCW) and Institutional Research and Planning. The survey was comprised of questions about factors impacting employees’ work, including caregiving responsibilities. It was available to respondents of any gender on all Ohio State campuses; participation was voluntary.

Women were the primary respondents for the study, with women representing 69% of faculty, 85% of staff.

Summary Report of Faculty & Staff COVID-19 Remote Work Experiences

Guidance for Supporting Caregivers during COVID-19

Overwhelmingly, respondents attested to the disproportionately gendered impact that COVID-19 is having on women and their professional development, especially for women of color and caregivers.

Data from the survey and the following recommendations aim to inform deans, chairs, supervisors, and other decision-makers in supporting employees and students who are providing care while balancing work responsibilities:

- Support staff in devising flexible arrangements under the terms of Flexible Work Policy 6.12. This Human Resources policy existed even before the pandemic and allows for employees and supervisors to negotiate changes to work scheduling and location, including “a compressed workweek, telecommuting or starting/ending times that change periodically.”

- Learn more about the Families First Coronavirus Response Act and other leave options available to caregivers when “full-time in-person learning” is unavailable for minor children.

- Clarify your unit’s practices to allow faculty, staff, and student parents to bring their minor children to campus in the occasional absence of alternative childcare.

- Avoid requiring employees or students to always turn on their cameras during meetings and classes. Caregivers may need additional privacy to care for loved ones (including by nursing) while fulfilling work responsibilities. Participants may still be engaged while not appearing on video.

- Schedule meetings and events at times less likely to conflict with school drop-off/pick-up times or the beginning and end of virtual school days. When possible, record meeting notes and events to later circulate to people who must be absent.

- Normalize the practice of male colleagues taking parental leave and performing an equal share of caregiving and household duties. Do not tolerate inappropriate office jokes that perpetuate gender stereotypes and unequal household labor.

- Recognize how the budget constraints of COVID-19 responses are curtailing professional development opportunities, including travel, conference attendance, and networking, for staff and faculty in 2020. Aim to maintain or restore those opportunities, when possible, to support women and caregivers in continuing their career progression.

- Enable researchers to include childcare expenses as a budget line item for grant funding, allowing scholars to have more uninterrupted time from parenting.

- Request or allow a no-cost extension for grant funding that is set to expire in 2020. Grant sponsors or research officers can proactively reach out to scholars to offer resources for them to defer, extend or restart their research agendas.

- Recognize that the pandemic’s disruptions may have a multi-year impact on scholars’ research productivity. Ohio State has extended the tenure clock for early career faculty by one year. Yet delays in the research, peer-review and publication pipeline may extend beyond a single academic year.

- Value multiple forms of scholarly productivity. Preliminary assessments suggest that the submission rate for peer-reviewed journals is declining during the pandemic, especially among women. Still, scholars continue to make important interventions in academic and public conversations through interviews, media appearances, editorials and short works that showcase their expertise. Value this work favorably in annual reviews and promotion dossiers.

- Include caregivers and their concerns in decision-making for return-to-campus and post-pandemic responses. Consult The Women’s Place as a resource when convening diverse representatives for university committees. Through its yearly Staff Leadership Series (SLS) and President and Provost’s Leadership Institute (PPLI), The Women’s Place has a long history of equipping women and underrepresented staff and faculty as proven and emerging leaders. Tap into the network of The Women’s Place to bring a range of voices and insights to strategic planning.

Highlighted Survey Results

- Staff and faculty alike attested to the challenges of working from home while providing care for children, elders, or other individuals with special needs. Among staff, 20% said that caregiving responsibilities frequently or very frequently impacted their work.

- Staff women estimated that they perform 66% of household caregiving on average. By contrast, male staff estimate that they perform 45%. Numbers among faculty respondents were similar.

- Faculty women of color estimated that they perform 69% of household caregiving on average, a higher rate compared to other women performing 62% of caregiving.

- Fifty-eight percent of faculty felt that their workload increased during the telework period, spending an average of 43% of their time on teaching and student support. By comparison, they focused on research only 17% of the time.

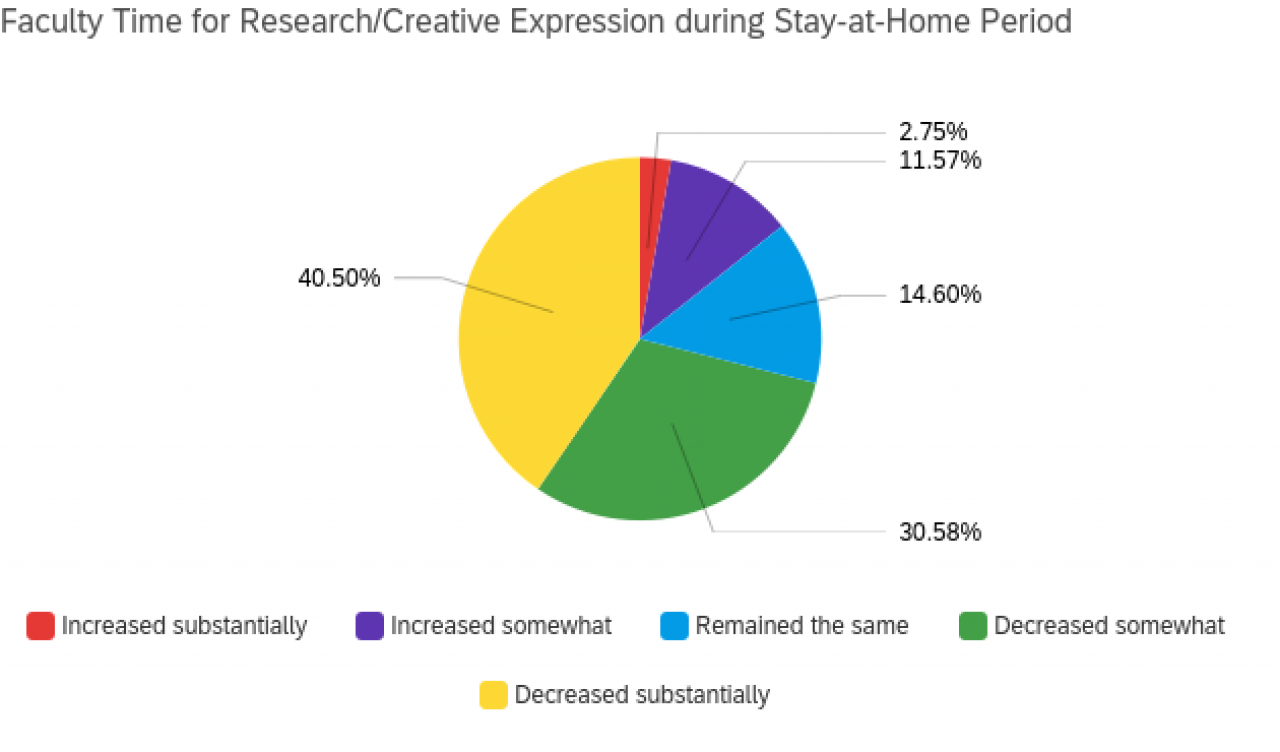

- Seventy-one percent of faculty replied that they had less time for research and creative expression during the pandemic.

- Faculty were twice as likely as staff to already have been in the habit of working from home before COVID-19 closures, and 79% of faculty would like the option to continue working remotely.

- Many staff were working remotely for the first time (42%), but as many as 87% would like the option to continue to work from home when the university returns to full operationality.

- Fifty-four percent of staff respondents expressed concerns about job security.

- Strikingly, by mid-May 2020, about 9-10 weeks into the stay-at-home period, most respondents said that they had not been impacted by personal illness or loss and grief. Yet they remained concerned about their health and the well-being of loved ones.

For more ways to address the impact of COVID-19 on women’s work and well-being, see our webinar on "The Caregiving Crisis" and visit our COVID-19 Resources page.